|

|

Post by imperfectgolfer on Mar 8, 2023 12:27:18 GMT -5

Watch this AMG video on left shoulder motion during the backswing action The following capture image best depicts their teaching principle.  MG placed his hand against SW's lead shoulder at address. SW then performed his standard backswing action. Note that SW's lead shoulder has moved away from the target by ~12" by P4.

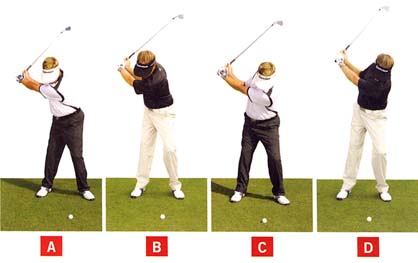

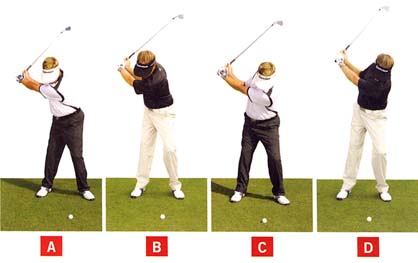

Most importantly, note that SW's head has moved slightly away from the target and that he is performing a rightwards-centralised backswing loading pattern. Note that SW is not using an arch-extension maneuver to move his upper swing center towards the center of his stance and that his upper swing center only moves targetwards to a small degree in his later backswing action because he rotates his shoulders >90 degrees clockwise. Note how flat his shoulder turn angle is relative to the ground - and it measures ~40 degrees when viewed from DTL - due to the fact that he does not add an additional amount of left lateral bending, which would cause his left shoulder socket to move more steeply groundwards. Here are the 4 different patterns of upper torso loading during a backswing action. A = Rightwards upper torso loading pattern B = Rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern. C= Leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern. D= Leftwards upper torso loading pattern (=reverse pivoting). I am changing my thinking about which upper torso loading pattern is desirable. I strongly favored the rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern, but I also stated that the leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern was equally acceptable. I now cannot see any advantage to using a leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern - even though it is workable as seen in S&T golfers. I now think that getting the lead shoulder far away from the target by P4 is desirable - as seen in pattern A and B. I now think that pattern A is specifically recommended for golfers who are so spine-inflexible that they cannot generate any torso-pelvic separation, while pattern B is recommended for the majority of pro/amateur golfers who can generate torso-pelvic separation.

What I specifically like about patterns A and B are two elements.

The first element is that it allows for a greater degree of lead shoulder motion in a targetwards direction during the P4 => P5.5 time period. Consider an example - featuring Dustin Johnson. Image 1 is at P4, image 2 is at P4.5 and image 3 is at P5. I have drawn a blue circle over his lead shoulder socket at P4 - note how far DJ has moved his lead shoulder away from the target between P1 => P4 as a result of performing a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern.

I have drawn a green circle over his lead shoulder socket at P4.5 and a red circle over his lead shoulder socket at P5.

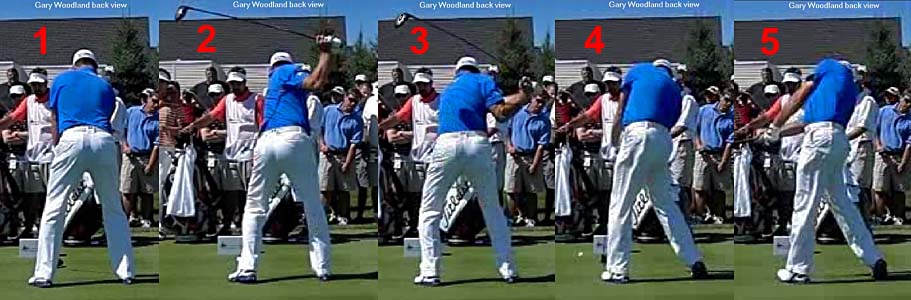

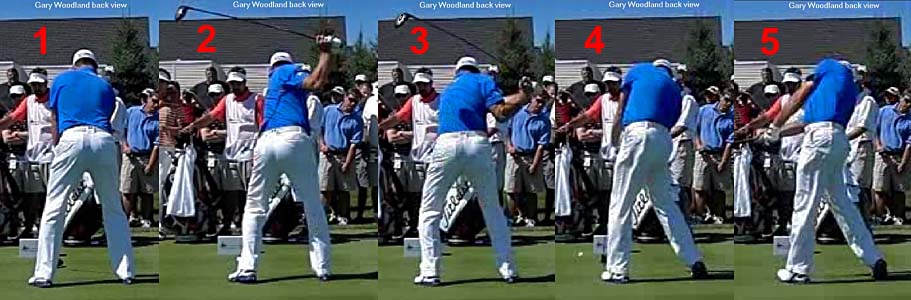

Note how much his lead shoulder socket can move targetwards between P4 => P5, which I think is very advantageous from a swing power perspective. Here is the S&T pattern. Image 1 is at P4 where the upper swing center is stacked over the lower swing center as a result of the S&T golfer using a leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern. Note that the lead shoulder has not moved very far away from the target between P1 => P4, which therefore limits its directional travel in a targetwards direction between P4 => P5. Another feature of a leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern that I do not favor is that it is generally associated with a leftwards pressure loading pattern of the feet so that a significant amount of the overall COP measurement (40 - 60%) is loaded over the lead foot at P4. That means that the golfer is more dependent on generating an early and large vertical GRF under the lead foot starting at P5 - P5.2 in order to efficiently rotate the pelvis counterclockwise during the downswing action. Although it is possible to rotate the pelvis efficiently using that pattern - as seen in S&T golfers and Milo Lines driver golf swing action - I think that it is biomechanically easier to rotate the pelvis more efficiently during the downswing by using a rightwards pelvic loading pattern as seen in Dustin Johnson's driver backswing action. Note that DJ manifests two phases of counterclockwise pelvic rotation - i) a hip-squaring phase between P4 => P5 due to the use of his right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles that can generate a high foot torque measurement when measured by a Swing Catalyst device and ii) a lead buttock motion back towards the tush line and also away from the target starting at ~P5.5 due to a lead leg straightening action that is usually associated with an increased vertical GRF measurement under the lead foot happening between P5 => P5.5. A S&T golfer is more dependent on ii) which requires the ability to generate a large vertical GRF under the lead foot (as seen in the "launcher" pattern recommended by Mike Adams/Terry Rowles). By contrast, a golfer who uses a rightwards pelvic loading pattern where 70 - 90% of the overall COP measurement is located under the trail foot at P4, is not dependent on generating a large vertical GRF measurement under his lead foot in order to generate an efficient counterclockwise pelvic rotation during the downswing action. Here is Gary Woodland's driver golf swing's backswing loading action. I have drawn red vertical lines upwards from the inside of his two feet. Note that his pelvis is shifted a little targetwards at address. Image 2 is at P4 - note that he shifted his pelvis rightwards, which means that he is using a rightwards pelvic loading pattern, and note that he is also using a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern. According to Swing Catalyst data, GW has 92% of his overall COP measurement under his trail foot at P4. Here is GW's Swing Catalyst graphs. Note that he uses a large amount of horizontal torque (magenta colored graph) to start his downswing action and a large amount of rotary torque (yellow graph) in his early downswing action, but he does not use much vertical GRF in his mid-downswing action (cyan graph). Gary Woodland's hip-squaring phase Image 1 is at P1, image 2 is at P3, image 3 is at P4 and image 4 is at P5.

I have drawn red lines alongside the outer border of his pelvis at P1.

Note how he manifests a rightwards pelvic loading pattern and a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern between P1 => P4. Note how much he moves his lead shoulder away from the target between P1 => P4.

Note how he shifts his pelvis targetwards between P4 => P5 while he simultaneously squares his pelvis using the standard hip-squaring action (presumably by using his right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles). Now, consider how efficiently he continues to rotate his pelvis between P5 => P7 without having to generate a large vertical GRF under his lead foot between P5 => P5.5.

Image 1 is at P1, image 2 is at P4, image 3 is at P5, and image 4 is at impact. Note how efficiently he rotates his pelvis counterclockwise between P5 => P7 without having to use the "launcher" pattern of generating a large vertical GRF under his lead foot in his mid-downswing action between P5 => P5.5. Jeff.

|

|

|

|

Post by playing18 on Mar 9, 2023 19:28:22 GMT -5

Dr. Mann, it’s always nice to read your golf swing papers.

I have a few questions/comments on this one.

—I can see how a rightwards-centralised backswing loading pattern can have a bit more distance to cover but this would only be due to the slight rightward sway motion during the backswing. Of course, the leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern would have the same lead shoulder excursion, otherwise. It just happens a bit more centralized, correct?

—There are three primary forces a given golfer can generate and use to increase club head speed: horizontal, rotational, and vertical force. Isn’t the best approach to use the force that the golfer is best at generating in the most efficient and effective way possible? If a player is best at generating vertical force, shouldn’t that be the one he or she seeks to use?

—Assuming a player has excellent vertical force production from the lead foot, I can’t see why he or she couldn’t turn the pelvis just as efficiently as a player who has a rightwards loading pattern and pushes from the trail foot. Again, doesn’t it depend on the individual player? GW does what he does because this is what he is best at, while a someone like Milo Lines does what he’s best at. Milo, a vertical force player, clearly has no problem rotating his pelvis.

—I don’t really trust those last photos of GW swaying that far outside his original address position. Seems like the camera is not stable in those set of photos. The first face-on photos look much more accurate.

—My guess is that a rightward-centralized loading pattern requires a lot of horizontal force and lateral speed/power to recenter in the allotted time from p4 to p7. Consequently, it may be better for older/slower players to move a shorter rightward distance from p1 to p4 that allows them to recenter properly by impact. For this reason, copying GW may not work unless the player has the same horizontal force/speed/power.

—A player with a rightward-centralized loading pattern who doesn’t recenter in time by p7 may run into other problems, such as OTT or tumbling issues to steepen the swing path to get the club to the ball, and/or an iron swing with a low point at or behind the ball instead of 4 inches in front of the ball.

Jim - playing18

|

|

|

|

Post by dubiousgolfer on Mar 9, 2023 20:13:24 GMT -5

Dr Mann There are some GEARS graphs concerning spine tilt on the link below for tour pros . I don't know how Erik Barzeski defines better players when he produced the average tilt (From P1-P7) using the driver in the below image. thesandtrap.com/forums/topic/112097-gears-pro-data-axis-tilt-drivers-and-irons/ At P4 the average tilt is about 4.5 degrees but I wouldn't know whether that would be defined as a rightwards or a rightwards-centralised loading pattern. Gears measures spinal tilt using a line from the middle of the base of the neck to the middle of the pelvis and then measuring its inclination with the horizontal . DG |

|

|

|

Post by imperfectgolfer on Mar 10, 2023 12:11:38 GMT -5

Jim, You wrote-: " I can see how a rightwards-centralised backswing loading pattern can have a bit more distance to cover but this would only be due to the slight rightward sway motion during the backswing. Of course, the leftwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern would have the same lead shoulder excursion, otherwise. It just happens a bit more centralized, correct?" No! I think that you are mixing-up pelvic loading patterns and upper torso loading patterns. It is possible to have a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern without pelvic sway to the right (as seen in Gary Woodland's and Mickey Wright's backswing's pelvic motional action). Here are two examples. Jack Nicklaus (when he was very young). Image 1 is at P1. I have drawn a blue circular marker over his left shoulder socket. Image 2 is at P4. I have drawn a red circular marker over his left shoulder socket. Note how much his left shoulder socket has moved away from the target between P1 => P4 due to the fact that he uses a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern that is associated with a large amount of upper torso rotation that causes the shoulders to turn ~100 degrees (> 90 degrees), thereby moving the left shoulder socket even further away from the target. Note that he uses a centralised pelvic loading pattern, so there is no sway of his pelvis in an away-from-the-target direction. There is also no upper torso sway motion, and he is simply rotating his upper torso around a rightwards tilted lumbar spine/lower thoracic spine while avoiding any arch-extension motion of his mid-upper thoracic spine.

Image 3 is at P5. Note that his left shoulder socket moves ~12" between P4 => P5.

Bryson DeChambeau Image 1 is at P1. I have drawn a green circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

Image 2 is at P4. I have drawn a red circular marker over his left shoulder socket. Note how much his left shoulder socket has moved away from the target between P1 => P4 due to the fact that he uses a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern that is associated with a large amount of upper torso rotation that causes the shoulders to turn ~120 degrees (>90 degrees), thereby moving the left shoulder socket even further away from the target.

Note that he uses a left-centralised pelvic loading pattern, so there is no sway of his pelvis in an away-from-the-target direction. There is also no upper torso sway motion, and he is simply rotating his upper torso around a rightwards tilted lumbar spine/lower thoracic spine while avoiding any arch-extension motion of his mid-upper thoracic spine. Image 3 is at P5. Note that his left shoulder socket moves >12" between P4 => P5.

I have never seen a pro golfer, who uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern, rotate their shoulders more than 90 degrees. Have you? They therefore must manifest less left shoulder motion in a targetwards direction between P4 => P5.

You wrote-: "There are three primary forces a given golfer can generate and use to increase club head speed: horizontal, rotational, and vertical force. Isn’t the best approach to use the force that the golfer is best at generating in the most efficient and effective way possible? If a player is best at generating vertical force, shouldn’t that be the one he or she seeks to use?" I do not think that these primary forces being exerted at the level of the feet's interaction with the ground directly correlate with a golfer's ability to generate a large clubhead speed at impact in a driver golf swing action. For example, a pro golfer only needs a large horizontal GRF being exerted under the trail foot if he uses a rightwards pelvic loading pattern (like Gary Woodland and Mickey Wright) and he does not need it if he uses a centralised or left-centralised pelvic loading pattern (like Jack Nicklaus and Bryson DeChambeau). Also, if a pro golfer is particularly adept at generating a large vertical GRF starting at P5 - P5.2 it can potentially increase the efficiency of release of PA#2 by increasing the "force" causing lead shoulder elevation after P5.5 and it can add a small amount of parametric acceleration to the swing power equation, but that ability does not increase the speed of release of PA#4.

You wrote-: "Assuming a player has excellent vertical force production from the lead foot, I can’t see why he or she couldn’t turn the pelvis just as efficiently as a player who has a rightwards loading pattern and pushes from the trail foot. Again, doesn’t it depend on the individual player? GW does what he does because this is what he is best at, while a someone like Milo Lines does what he’s best at. Milo, a vertical force player, clearly has no problem rotating his pelvis."

I cannot understand how a golfer, who only has excellent vertical GRF-generating ability and no rotary torque ability, can rotate the pelvis efficiently between P4 => P5.5 if he is not capable of generating a large amount of rotary torque.

I also do not think that Milo Lines is vertical force player, and I think that his greatest strength (from a swing power perspective) is his ability to generate a large amount of rotary torque.

Here is Milo's Swing Catalyst graphs at P4.

Note that he uses a centralised pelvic loading pattern and a vertical-centralised upper torso loading pattern - therefore he does not need to generate a large horizontal GRF under his trail foot to re-center between P4 => P5 - as noted in the following graph (showing him at his peak horizontal GRF measurement).

The following image shows Milo at his peak rotary torque GRF-generation time point.

Note that it happens at P5.5. Note that he is also generating a large amount of vertical GRF under his lead foot that can help him to move his lead buttocks back towards the tush line and help him to open his pelvis more - but I think that his rotary torque ability is his greatest strength from a swing power generation perspective. Here is a an image of Milo when his vertical GRF measurement is at its peak.

Note that it happens very late near impact, and it is too late to help him generate an increased clubhead speed via the launcher pattern of "jumping-up" through impact. In fact, note that Milo has 83% of his COP measurement under his lead foot at impact, which makes him a front-foot golfer, and not a reverse-foot golfer like Drew Cooper.

Here is an image of Drew Cooper at his peak vertical GRF measurement.

Note that DC is at his P5.2 position when his vertical GRF is at its peak value and that can explain why is a "jumper" (reverse-foot golfer).

You wrote-: "My guess is that a rightward-centralized loading pattern requires a lot of horizontal force and lateral speed/power to recenter in the allotted time from p4 to p7. Consequently, it may be better for older/slower players to move a shorter rightward distance from p1 to p4 that allows them to recenter properly by impact. For this reason, copying GW may not work unless the player has the same horizontal force/speed/power."

As I have previously explained, a lot of horizontal force is mainly needed if the pelvic loading pattern is rightwards, and not because a golfer chooses to use a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern. I used to think that older/slower golfers should therefore avoid using a rightwards pelvic loading pattern. I am now thinking in the opposite way - that senior golfers, who have zero hula hula flexibility, should use a rightwards pelvic loading pattern combined with a rightwards upper torso loading pattern. I will explain in a future post why I may be changing my thinking of this issue.

You wrote-: "A player with a rightward-centralized loading pattern who doesn’t recenter in time by p7 may run into other problems, such as OTT or tumbling issues to steepen the swing path to get the club to the ball, and/or an iron swing with a low point at or behind the ball instead of 4 inches in front of the ball." I agree that a golfer (eg. inflexible senior golfer) who does not recenter in time may hit "fat shots". However, I now think that the solution is not to avoid a rightwards pelvic loading pattern combined with a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern, but rather to improve his ability to re-center between P4 => P7 by deliberately adopting a rightwards pelvic loading pattern combined with a rightwards upper torso loading pattern. I am presently working on this new approach for my personal golf swing action.

Jeff.

|

|

|

|

Post by imperfectgolfer on Mar 10, 2023 12:31:27 GMT -5

Dr Mann There are some GEARS graphs concerning spine tilt on the link below for tour pros . I don't know how Erik Barzeski defines better players when he produced the average tilt (From P1-P7) using the driver in the below image. thesandtrap.com/forums/topic/112097-gears-pro-data-axis-tilt-drivers-and-irons/ At P4 the average tilt is about 4.5 degrees but I wouldn't know whether that would be defined as a rightwards or a rightwards-centralised loading pattern. Gears measures spinal tilt using a line from the middle of the base of the neck to the middle of the pelvis and then measuring its inclination with the horizontal . DG DG, You wrote-: " Gears measures spinal tilt using a line from the middle of the base of the neck to the middle of the pelvis and then measuring its inclination with the horizontal." I do not think that it's necessarily an useful measurement. Consider Jack Nicklaus' driver golf swing action.  Where does Eric make his measurement in image 2 at P4? I personally think that JN has a large amount of rightwards tilt of his lumbar spine/lower thoracic spine area of his mid-torso in image 2 and image 3.

Jeff.

|

|

|

|

Post by playing18 on Mar 10, 2023 15:07:02 GMT -5

Dr. Mann,

You wrote: I think that you are mixing-up pelvic loading patterns and upper torso loading patterns. It is possible to have a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern without pelvic sway to the right (as seen in Gary Woodland's and Mickey Wright's backswing's pelvic motional action).

I didn’t label the type of sway. I was referring to upper body sway as done by GW. But my intention was to say a player with a left-centralized pelvis/upper body loading pattern still has plenty of lead shoulder excursion based on pure body rotation. Rotation is rotation. Assuming the player rotates to the same degree, the only additional downswing lead shoulder advantage is the slight rightwards upper body sway or position. (In reality, it’s slight retained torso flexion with no added torso extension that moves or lines up the upper body slightly to the right at p4, as you know.) However, the left-centralized pelvic/upper body player still has plenty of downswing lead shoulder excursion and if this loading option works better for a given player, then that’s all that matters.

You wrote: I have never seen a pro golfer, who uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern, rotate their shoulders more than 90 degrees. Have you? They therefore must manifest less left shoulder motion in a targetwards direction between P4 => P5.

Are saying a very flexible LPGA players couldn’t rotate over 90-degrees using a left-centralized pelvis/upper body loading pattern? Why not? It would be more of a choice than an inability. Plus, these are not set categories, it involves a continuum. A player could easily add in some spinal extension across the spectrum, from low to high. There are certainly more than four simple loading/pivot categories.

I’ll say it again: There are three primary forces a given golfer can generate and use to increase club head speed: horizontal, rotational, and vertical force. Isn’t the best approach to use the force that the golfer is best at generating in the most efficient and effective way possible? If a player is best at generating vertical force, shouldn’t that be the one he or she seeks to use?

I obviously meant that all three are important and contribute. There is no force that isn’t important. A low vertical force might be low but it still contributes to the whole, just not like a high vertical force. Lower force simply means lower club head speed. This doesn’t imply that a given force doesn’t contribute in some positive way to the swing.

You wrote: I do not think that these primary forces being exerted at the level of the feet's interaction with the ground directly correlate with a golfer's ability to generate a large clubhead speed at impact in a driver golf swing action.

I don’t understand what you mean by this. Swing on a sheet of ice versus on stable ground. GRFs are obviously correlated with club head speed. And, all three GRFs contribute and are important. BTW, long-drive competitors try to increase all three GRFs because all three contribute. Of course, GW would hit the ball farther if he could generate more vertical force, but he still smashes it with the horizontal and rotational force he does generate. But, again, the relatively low vertical force GW generates is still helpful in some way and still probably contributes to his club head speed. It’s just that he depends mostly on his high horizontal and rotational force generation to make him a PGA pro.

You wrote: I cannot understand how a golfer, who only has excellent vertical GRF-generating ability and no rotary torque ability, can rotate the pelvis efficiently between P4 => P5.5 if he is not capable of generating a large amount of rotary torque.

Every player generates all three GRFs. Yes, the higher torque or rotational capacity, the better the torso rotation from p4 to p5.5. But, like you said in your post, there is probably some overlap where vertical forces can indirectly help to open the pelvis at the same time.

You wrote: I also do not think that Milo Lines is vertical force player, and I think that his greatest strength (from a swing power perspective) is his ability to generate a large amount of rotary torque.

I did not say Milo didn’t generate large torque forces. I only said he is vertical force player. Obviously, he is also a huge rotational force player. And, he also generates some horizontal force…it’s just not a dominant force for him. But all three contribute to club head speed on every swing, and all three are generated.

You wrote: I agree that a golfer (eg. inflexible senior golfer) who does not recenter in time may hit "fat shots". However, I now think that the solution is not to avoid a rightwards pelvic loading pattern combined with a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern, but rather to improve his ability to re-center between P4 => P7 by deliberately adopting a rightwards pelvic loading pattern combined with a rightwards upper torso loading pattern.

The solution is do what works for the given player. It doesn’t matter what anybody else does. It usually helps to copy a pro, but not always. If the player finds a left-centralized pelvic/upper body rotation is best for him or her, then this is the answer, always. If a player is best at generating horizontal force, then he shouldn’t do anything that makes that go down unless it makes the other GRFs go up. This apparently happened to Luke Donald. He is reportedly really good at generating horizontal force but was focusing on swing changes that caused a loss of his dominant force. Then, recently he went back to a swing that promotes more horizontal forces and it significantly increased his club head speed and driving distance. So, it all depends on the player. Milo and Luke are on different swing planets and should never try to be like one another or copy one another. This concept applies to every player. There is no one right to swing. It all depends on what works best for the player.

|

|

|

|

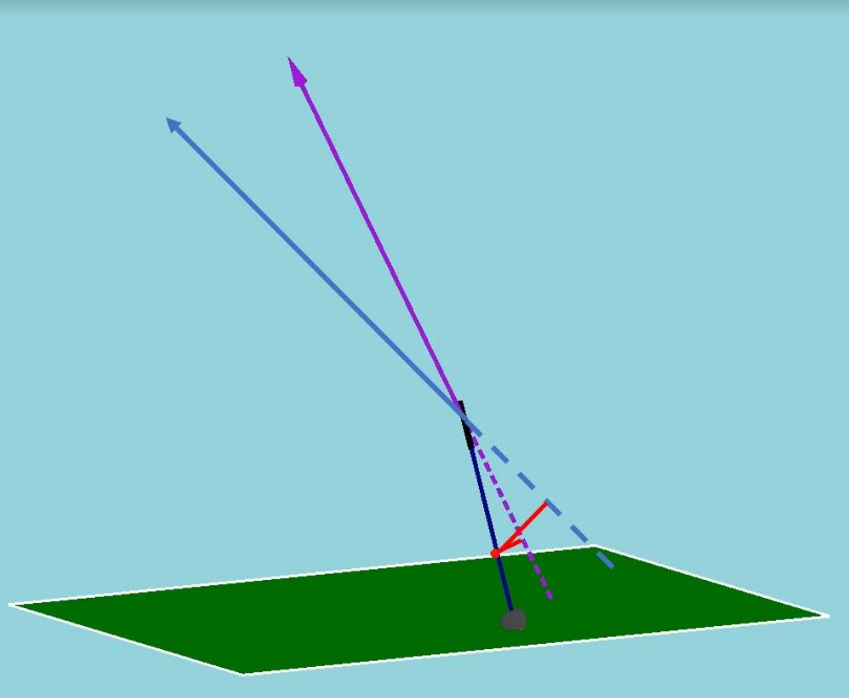

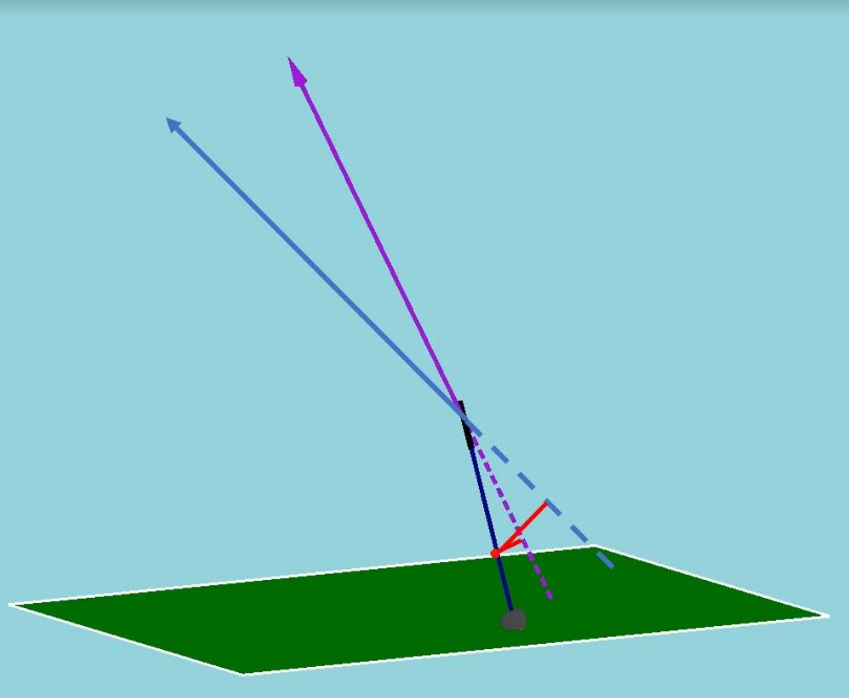

Post by dubiousgolfer on Mar 10, 2023 18:27:04 GMT -5

Hi Jim I'm not 100% sure that GRF's are correlated with clubhead speed although Dr Kwon seems to think so . There are others who have found no correlation, see some excerpts below: Could not find any energy being transferred between body segments in some proximal to distal sequence (Brady C Anderson). Most of the work done by body segments is to move themselves, not get transferred between segments (Work and Power Analysis of the Golf Swing- Dr Steven Nesbit) Could not find any correlation between ground reaction forces and clubhead speed (Effect of Horizontal Ground Reaction Forces during the Golf Swing: Implications for the Development of Technical Solutions of Golf Swing Analysis :Maxime Bourgain, Christophe Sauret, Grégoire Prum, Laura Valdes-Tamayo, Olivier Rouillon, Patricia Thoreux, and Philippe Rouch). Even Dr Scott Lynn emailed me the following, but its a hypothesis. ------------------------------------------------------------------- Thanks so much for your email. You ask some really good questions that I don’t think anyone has the answers to yet. I’m not aware of any published work that has been done to date where the GRFs have been measured on the same swings where club inverse dynamics analyses were run so that the calculated club/hands kinetic values could be related to the measured GRFs. Hopefully this type of work will happen soon as this would really help our understanding of golf swing mechanics. My hypothesis would be that creating more horizontal braking GRF from the ground could result in some of that force (directed away from the target) being transferred through the body and to the club in the late downswing (as this is when we see the peak horizontal braking GRF in high speed swingers). It is interesting to note that in a few of the fastest long drive competitors in the world that I have had the opportunity to measure, the horizontal braking GRF peaks at the same time as the vertical GRF. If the golfer is able to peak the vertical and horizontal braking GRFs at the same time and transfer these forces through the body to the club, this could result in the net force on the club having a large magnitude and being directed more away from the target in the late downswing, thus increasing the moment arm between the line of action of the net force and the center for mass of the club. This would increase the in plane moment of force during the late downswing, when Dr. Mackenzie’s work has shown us that this particular moment is dominant in speeding up the club (the CoM of the club trying to “line up” with the line of action of that force vector). I have made a quick figure using one of Dr. Mackenzie’s animations to illustrate my point (see attached). If the purple vector is the net force applied to the club in the late downswing by a golfer with limited horizontal braking force, the blue vector would be my hypothesized net force vector applied to the club if horizontal braking GRF was increased in the late downswing. By using the horizontal braking GRF to lean this net force vector away from the target more, this would increase the moment arm distance (estimated in red…hard to do in 2D but you get the idea) and hence the in-plane moment of force and speed the club up as it heads into impact. Again this is just a hypothesis at this point and I’m open to other ideas and/or being proven wrong.  --------------------------------------------------------- DG |

|

|

|

Post by imperfectgolfer on Mar 11, 2023 11:07:02 GMT -5

Jim, You wrote-: " But my intention was to say a player with a left-centralized pelvis/upper body loading pattern still has plenty of lead shoulder excursion based on pure body rotation. Rotation is rotation. Assuming the player rotates to the same degree, the only additional downswing lead shoulder advantage is the slight rightwards upper body sway or position. (In reality, it’s slight retained torso flexion with no added torso extension that moves or lines up the upper body slightly to the right at p4, as you know.) However, the left-centralized pelvic/upper body player still has plenty of downswing lead shoulder excursion and if this loading option works better for a given player, then that’s all that matters." Here are capture images showing the left shoulder motion of two S&T golfers who use a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern.

Charlie Wi

Image 1 is at P1 - I have drawn a yellow circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

Image 2 is at P4 - I have drawn a red circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

Image 3 is at P5 - I have drawn a green circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

Troy Matteson

Image 1 is at P1 - I have drawn a yellow circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

Image 2 is at P4 - I have drawn a red circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

Image 3 is at P5 - I have drawn a green circular marker over his left shoulder socket.

By comparison, here is Dustin Johnson's left shoulder motion between P4 => P5.

Image 1 is at P4 and image 3 is at P5.

You may think that the difference in left shoulder excursion between P4 => P5 is not significant, but I don't know why you would harbor that opinion.

You wrote-: "I’ll say it again: There are three primary forces a given golfer can generate and use to increase club head speed: horizontal, rotational, and vertical force. Isn’t the best approach to use the force that the golfer is best at generating in the most efficient and effective way possible? If a player is best at generating vertical force, shouldn’t that be the one he or she seeks to use?"

You are presumably referring to forces that are measured at the level of the feet via a Swing Catalyst device. First of all, there is a fundamental question as to whether those GRF measurements are primary forces or merely reflective of what is happening at the level of the foot's interaction with the ground when a golfer executes his golf swing action in a biomechanically efficient manner? Secondly, how would you argue that Milo's vertical GRF measurement causally increases his driver's clubhead speed at impact considering that it peaks very late in his downswing near impact (and not near P5.5 as seen in Drew Cooper's driver swing). Thirdly, if a golfer is physically capable of producing a large amount of horizontal GRF at P4, how would be it be beneficial if he uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern swing technique (like Charlie Wi). Finally, DG has pointed out a statement made by Scott Lynn that claims that there is no scientific evidence that shows that there is any correlation between Swing Catalyst measurements of horizontal, rotary and vertical GRFs and the forces/torques that the golfer is applying to the club handle during the downswing. I also think that if a golfer gets measured on a Swing Catalyst device, where he simply tries to increase his horizontal, rotary and vertical GRF measurements as a primary goal, that he may not necessarily be doing anything useful to increase his clubhead speed or improve his golf swing biomechanics.

You wrote-: "Of course, GW would hit the ball farther if he could generate more vertical force, but he still smashes it with the horizontal and rotational force he does generate."

What "evidence" do you have to support that opinion?

You wrote-: "The solution is do what works for the given player. It doesn’t matter what anybody else does. It usually helps to copy a pro, but not always. If the player finds a left-centralized pelvic/upper body rotation is best for him or her, then this is the answer, always. If a player is best at generating horizontal force, then he shouldn’t do anything that makes that go down unless it makes the other GRFs go up."

If a golfer uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern because he believes that it works best for him, how do you exclude the possibility that he has simply not learned how to efficiently perform a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern swing action?

Jeff.

|

|

|

|

Post by playing18 on Mar 11, 2023 11:16:47 GMT -5

Thanks for the reply DG. It is amazing the ability of you and Dr. Mann in studying and analyzing the golf swing in such infinite detail. Definitely out of my league or not my prime point of interest, but nonetheless impressive and interesting.

Isn’t this a matter of correlational research versus technical causation research? Certainly, Dr. Lynn believes in the value of Swing Catalyst and that increasing GRFs is obviously correlated and important in increasing club head speed.

Are you saying there is logic to suggest that players with exceptionally high GRFs could have low maximum club head speeds or players with exceptionally low GRFs could have high maximum club head speeds. If so, what is the rationale for this?

Is it because science hasn’t provided the causation evidence or because there is no logical cause and effect?

Jim -playing18

|

|

|

|

Post by dubiousgolfer on Mar 11, 2023 13:09:44 GMT -5

Hi Jim

"Are you saying there is logic to suggest that players with exceptionally high GRFs could have low maximum club head speeds or players with exceptionally low GRFs could have high maximum club head speeds. If so, what is the rationale for this?"

I honestly don't know until further research is conducted as per Dr Scott Lynn's email to me. I can suspect that it would be an incredibly complex and expensive bit of research to determine cause and effect. For example, I am assuming you saw Chris Como jumping from a height into a swimming pool while still being able to perform a swing while weightless? I'm unsure what clubhead speed he created but it obviously didn't look like a tour pro golf swing. But say he was able to produce high club head speed without GRFs, what would that suggest? Are some GRF's (or a portion of them) reflected back from the ground back up through the body in some fashion that could directly/indirectly assist in the creation of forces applied via the hands on the grip? Could some of the GRF's just be 'constraint' type forces to prevent the golfers body segments impeding other musculature activities from accelerating/directing the club?

*****Note: Constraining forces limit motional degrees of freedom.******

We do seem to have a contradiction between what Dr Kwon told me (via you-tube comments) regarding his own research article (below) and the one I mentioned in my earlier post.

Han, K.H., Como, C., Kim, J., Lee, S., Kim, J., Kim, D.K., Kwon, Y.-H. (2019). Effects of the golfer-ground interaction on clubhead speed in skilled male golfers. Sports Biomechanics, 18(2), 115-134. doi:10.1080/14763141.2019.1586983

The main difference being that Dr Kwon didn't run any correlation tests between the components of the grfs within the 'functional swing plane' vs clubhead speed.

DG

|

|

|

|

Post by playing18 on Mar 11, 2023 17:32:13 GMT -5

DG, I don’t recall CC’s jump from the high dive and attempted motion looking anything close to a normal golf swing. Same with the guy on the YouTube video taking a swing on the iced over lake. Any normal golf swing pattern he had was certainly completed before he slipped and broke through the ice.

I think it’s an obvious conclusion and it would be easy to show a significant and strong correlation between GRFs and club head speed. Swing on ice versus swing on the ground. Compare long drivers versus beginners. Swing suspended off the ground versus on stable ground. But, I don’t think this is what Scott Lynn is talking about in his email. I guess you could ask him, but I’m pretty sure he is only referring to technical cause and effect research to see possible hidden details. He obviously values his force plates and knows GRFs are important in the golf swing and during golf swing instruction. Plus, a simple correlational study on GRFs and club head speed would never be published in a rigorous biomechanics journal.

Is there more to know and understand? Of course. But on a basic level, we don’t need science to tell us that GRFs are important.

I believe GRFs are simply an indirect marker to predict what might be happening inside a player’s muscles when the feet are stable and on firm ground. The higher the GRF, the greater is the muscle activation. The more muscle activation, the greater is the potential that this force can be used to move the body efficiently to power the golf swing. Muscle force activation precedes the GRFs and the movement. Muscle force generation is invisible and its impossible to determine its exact purpose and magnitude. Assessing GRFs is a proxy for what the player’s muscles are doing. It’s simply an indirect way to show this. Not perfect, but educational and better than nothing.

GRFs assessments can 1) motivate a player to exercise to improve muscle activation. Do we need more science before we recommend proper exercise? No. 2) GRF data can encourage a player to focus on his or her dominant force and swing accordingly, with more of a horizontal, rotational, vertical, or combination swing type. Do we need more science before we can recommend this? No. It’s a matter of finding the swing that provides the highest power and accuracy for the individual player, and to identify the ideal GRF profile that matches the best golf shot performance data. The GRF data, whatever it is, will provide a force-print that corresponds to the optimal swing. No group research study can indicate what is best for an individual golfer. It can only be done on an individual basis. 3) GRF data can indicate the best and most repeatable sequence of force generation for a given player, which relates to swing motion timing and shot consistency. The misfiring of muscles will show up on the GRF graph and correlate with poor golf swing performance. Improving muscle coordination will lead to improved GRF consistency and ultimately golf shot consistency.

I don’t see how doing technical cause and effect GRF research could change or improve any of these instructional benefits. It might be interesting to the golf swing theorist but I don’t see how it could improve how a golf instructor currently uses GRF data on the lesson tee.

Jim - playing18

|

|

|

|

Post by dubiousgolfer on Mar 11, 2023 19:10:49 GMT -5

Hi Jim

Grf's are obviously important as shown when swinging on a surface with friction compared to frictionless. They are a reaction to muscular activation (maybe not including isometric contractions) but I cannot say for certain which groups of muscles might be causing them or whether other patterns/sequences of muscular activation can recreate identical graphs seen on the Swing Catalyst.

Only time will tell how the optimisation of grfs for specific golfers might improve their swing mechanics and I'm sure scientists like Dr Scott Lynn and Dr Kwon are busy collecting the data.

With regards understanding more about cause and effect , I do think it could be useful because, if no correlation found , then a golfer might be putting unnecessary stresses on his/her body during the golf swing.

DG

|

|

|

|

Post by playing18 on Mar 12, 2023 12:18:46 GMT -5

Finally playing golf tomorrow at my home course after a wild winter. The weather is still unsettled but spring is almost here!

We’ve beat this topic enough but here is my response to Dr. Mann:

JM: You may think that the difference in left shoulder excursion between P4 => P5 is not significant, but I don't know why you would harbor that opinion.

P18: There’s nothing wrong with getting more lead shoulder excursion, if it works for the player. It’s also not wrong to have less if this is the player’s ideal swing style. But, as you illustrated, CW and TM, still get plenty. The more lead shoulder excursion the higher the potential swing speed, all else being equal, but this doesn’t mean everyone should copy DJ. It always depends on what works for the specific player.

JM: First of all, there is a fundamental question as to whether those GRF measurements are primary forces or merely reflective of what is happening at the level of the foot's interaction with the ground when a golfer executes his golf swing action in a biomechanically efficient manner?

P18: True, GRFs are an estimate or proxy for muscle activation and may not entirely explain where every specific force is coming from within the body (etc. etc.), but this certainly doesn’t mean that GRFs provide conflicting or detrimental data. As I mentioned, there are several inherent benefits for measuring GRF data and it can certainly be a useful guide in correlating what GRFs force-prints match up with a given player’s best golf shot performance (ball speed, accuracy, and consistency).

JM: Secondly, how would you argue that Milo's vertical GRF measurement causally increases his driver's clubhead speed at impact considering that it peaks very late in his downswing near impact (and not near P5.5 as seen in Drew Cooper's driver swing).

P18: Most golfers do learn that the expression of the their GRFs are too late, which is essential information. And, like all of us, maybe Milo could improve his 330 yard drives, but the same applies. If Milo is happy with his piped long drives, then his current GRF force-print gives him the feedback he needs: Keep doing what you’re doing! If instead he hits his drive 230 yards, then he might need to express his vertical force earlier. But, most likely Milo is doing just fine and his vertical GRF expression is contributing to his powerful club head speed. Same with Mr. Cooper. If he’s happy with his golf performance, then he can be happy with his GRF profile. And if a player isn’t happy with his or her golf performance and GRF force-print? The player better start exercising to get stronger and find ways to improve the golf swing. And, I bet the GRF profile and golf performance outcomes will both change and improve in a stepwise manner. If not, who cares. The player has improved and is playing better golf. But, it would be an interesting research study to see how improvements in a player’s strength or golf performance change the GRF profile from Pre to Post. This is the type of research I’d like to see conducted. However, this doesn’t mean the research must be done before we use force plates in our golf improvement process.

JM: Thirdly, if a golfer is physically capable of producing a large amount of horizontal GRF at P4, how would be it be beneficial if he uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern swing technique (like Charlie Wi).

P18: It normally wouldn’t be a good idea unless the player gets even better golf performance results using rotational and vertical forces. Could happen, but it’s probably a rare exception. Like Luke Donald, if you’re good at horizontal force production, it usually best to use it and perform a golf swing that promotes it.

JM: Finally, DG has pointed out a statement made by Scott Lynn that claims that there is no scientific evidence that shows that there is any correlation between Swing Catalyst measurements of horizontal, rotary and vertical GRFs and the forces/torques that the golfer is applying to the club handle during the downswing. I also think that if a golfer gets measured on a Swing Catalyst device, where he simply tries to increase his horizontal, rotary and vertical GRF measurements as a primary goal, that he may not necessarily be doing anything useful to increase his clubhead speed or improve his golf swing biomechanics.

P18: As I said earlier, I don’t agree that this is what Scott Lynn meant in his email. And, I agree that any attempts to increase GRFs without concomitant improvements in golf performance is silly. Of course, golf improvement is the only outcome that matters.

JM: You wrote-: "Of course, GW would hit the ball farther if he could generate more vertical force, but he still smashes it with the horizontal and rotational force he does generate."

What "evidence" do you have to support that opinion?

P18: I only have circumstantial evidence that DC hits it farther than Milo because he has earlier and even higher vertical force than him (I assume). Only makes sense.

JM: If a golfer uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern because he believes that it works best for him, how do you exclude the possibility that he has simply not learned how to efficiently perform a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern swing action?

P18: Unfortunately this is not possible unless you have GRF data and/or performance data showing that one works better than the other. The worse case scenario is to have neither and cluelessly try random ideas with no systematic approach. I think Einstein made a statement about this once.

Jim - playing18

|

|

|

|

Post by imperfectgolfer on Mar 12, 2023 12:48:19 GMT -5

Finally playing golf tomorrow at my home course after a wild winter. The weather is still unsettled but spring is almost here! We’ve beat this topic enough but here is my response to Dr. Mann: JM: You may think that the difference in left shoulder excursion between P4 => P5 is not significant, but I don't know why you would harbor that opinion. P18: There’s nothing wrong with getting more lead shoulder excursion, if it works for the player. It’s also not wrong to have less if this is the player’s ideal swing style. But, as you illustrated, CW and TM, still get plenty. The more lead shoulder excursion the higher the potential swing speed, all else being equal, but this doesn’t mean everyone should copy DJ. It always depends on what works for the specific player. JM: First of all, there is a fundamental question as to whether those GRF measurements are primary forces or merely reflective of what is happening at the level of the foot's interaction with the ground when a golfer executes his golf swing action in a biomechanically efficient manner? P18: True, GRFs are an estimate or proxy for muscle activation and may not entirely explain where every specific force is coming from within the body (etc. etc.), but this certainly doesn’t mean that GRFs provide conflicting or detrimental data. As I mentioned, there are several inherent benefits for measuring GRF data and it can certainly be a useful guide in correlating what GRFs force-prints match up with a given player’s best golf shot performance (ball speed, accuracy, and consistency). JM: Secondly, how would you argue that Milo's vertical GRF measurement causally increases his driver's clubhead speed at impact considering that it peaks very late in his downswing near impact (and not near P5.5 as seen in Drew Cooper's driver swing). P18: Most golfers do learn that the expression of the their GRFs are too late, which is essential information. And, like all of us, maybe Milo could improve his 330 yard drives, but the same applies. If Milo is happy with his piped long drives, then his current GRF force-print gives him the feedback he needs: Keep doing what you’re doing! If instead he hits his drive 230 yards, then he might need to express his vertical force earlier. But, most likely Milo is doing just fine and his vertical GRF expression is contributing to his powerful club head speed. Same with Mr. Cooper. If he’s happy with his golf performance, then he can be happy with his GRF profile. And if a player isn’t happy with his or her golf performance and GRF force-print? The player better start exercising to get stronger and find ways to improve the golf swing. And, I bet the GRF profile and golf performance outcomes will both change and improve in a stepwise manner. If not, who cares. The player has improved and is playing better golf. But, it would be an interesting research study to see how improvements in a player’s strength or golf performance change the GRF profile from Pre to Post. This is the type of research I’d like to see conducted. However, this doesn’t mean the research must be done before we use force plates in our golf improvement process. JM: Thirdly, if a golfer is physically capable of producing a large amount of horizontal GRF at P4, how would be it be beneficial if he uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern swing technique (like Charlie Wi). P18: It normally wouldn’t be a good idea unless the player gets even better golf performance results using rotational and vertical forces. Could happen, but it’s probably a rare exception. Like Luke Donald, if you’re good at horizontal force production, it usually best to use it and perform a golf swing that promotes it. JM: Finally, DG has pointed out a statement made by Scott Lynn that claims that there is no scientific evidence that shows that there is any correlation between Swing Catalyst measurements of horizontal, rotary and vertical GRFs and the forces/torques that the golfer is applying to the club handle during the downswing. I also think that if a golfer gets measured on a Swing Catalyst device, where he simply tries to increase his horizontal, rotary and vertical GRF measurements as a primary goal, that he may not necessarily be doing anything useful to increase his clubhead speed or improve his golf swing biomechanics. P18: As I said earlier, I don’t agree that this is what Scott Lynn meant in his email. And, I agree that any attempts to increase GRFs without concomitant improvements in golf performance is silly. Of course, golf improvement is the only outcome that matters. JM: You wrote-: "Of course, GW would hit the ball farther if he could generate more vertical force, but he still smashes it with the horizontal and rotational force he does generate." What "evidence" do you have to support that opinion? P18: I only have circumstantial evidence that DC hits it farther than Milo because he has earlier and even higher vertical force than him (I assume). Only makes sense. JM: If a golfer uses a left-centralised upper torso loading pattern because he believes that it works best for him, how do you exclude the possibility that he has simply not learned how to efficiently perform a rightwards-centralised upper torso loading pattern swing action? P18: Unfortunately this is not possible unless you have GRF data and/or performance data showing that one works better than the other. The worse case scenario is to have neither and cluelessly try random ideas with no systematic approach. I think Einstein made a statement about this once. Jim - playing18 Jim, I totally disagree with your opinions. I will not dissect every opinion that you expressed to explain why I disagree, and I will only focus on two of your opinions to express my disagreements. You wrote-: " True, GRFs are an estimate or proxy for muscle activation and may not entirely explain where every specific force is coming from within the body (etc. etc.), but this certainly doesn’t mean that GRFs provide conflicting or detrimental data. As I mentioned, there are several inherent benefits for measuring GRF data and it can certainly be a useful guide in correlating what GRFs force-prints match up with a given player’s best golf shot performance (ball speed, accuracy, and consistency)." I believe that a golfer's GRF force-prints do not correlate with the efficiency of his golf swing biomechanics (in terms of muscle activation timing or muscular force production) and I especially do not think that they correlate with his best shot performance in terms of ball speed or accuracy or consistency. I definitely do not believe that looking at any pro golfer's GRF force-prints can be considered to be an useful guide to understanding why he is performing the golf swing well from a biomechanical perspective because I think that "good" golf swing biomechanics do not have any direct/consistent correlation with any Swing Catalyst GRF measurements happening at the level of the foot's interaction with the ground.

You wrote-: "Like Luke Donald, if you’re good at horizontal force production, it usually best to use it and perform a golf swing that promotes it."

This statement represents the width of the vast difference in our thinking on this issue. You seem to be thinking that if a pro golfer is good at producing a particular GRF force (eg. horizontal GRF) that he should use it and modify his golf swing in order to promote use of that force. I totally disagree with that line of thinking!

Jeff.

|

|

|

|

Post by dubiousgolfer on Mar 12, 2023 12:57:14 GMT -5

I think the same can be said of the kinematic sequence because there are no guarantees that the golfer's swing mechanics will be ideal just because he has a perfect kinematic sequence.

Check out this video below.

DG

|

|